From The Optimist Magazine

Fall 2015

Commentary by Fred Pearce, a London-based environmental writer, is author of numerous books, most recently The New Wild: Why Invasive Species Will Be Nature’s Salvation, from which this is excerpted.

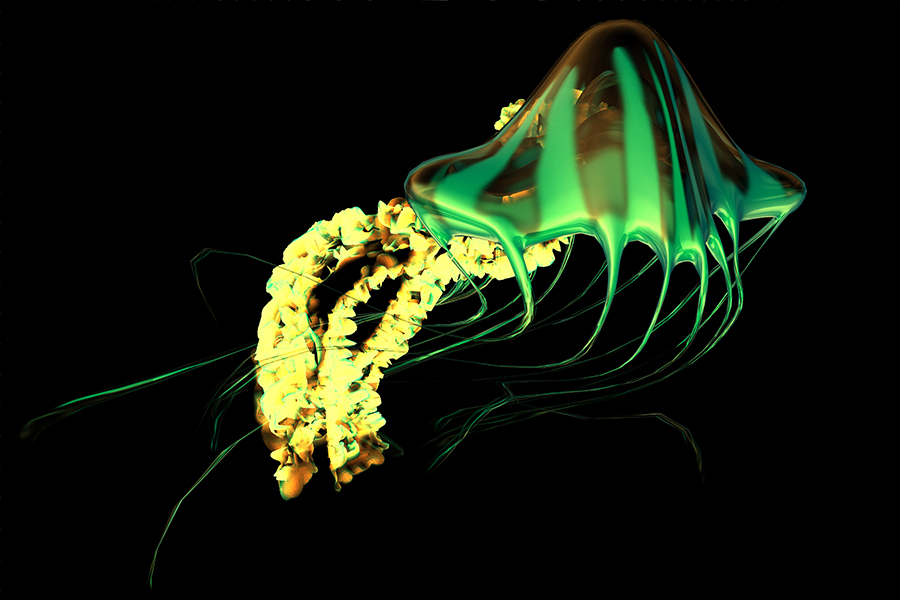

Rogue rats, predatory jellyfish, suffocating super-weeds, wild boar, snakehead fish wriggling across the land—alien species are taking over. Nature’s vagabonds, ruffians and carpetbaggers are headed for an ecosystem near you. These biological adventurers are traveling the world in ever greater numbers, hitchhiking in our hand luggage, hidden in cargo holds, stuck to the bottom of ships and migrating to keep up with climate change. They cruise the planet and set up home in distant lands. Some run riot, massacring local species, trashing their new habitats and spreading diseases.

We all like a simple story with good guys and bad guys. And aliens always make easy enemies. So the threat of foreign species invading fragile environments and causing ecological mayhem gets our attention. Conservationists have for half a century been battling to hold back the tide of aliens. They call them the second-biggest threat to nature, after habitat loss.

Yet, while I was researching my new book, The New Wild, many ecologists who actually study nature told me that they felt conservationists were getting the aliens wrong. And worse, that their efforts to keep out all foreign invaders of ecosystems might often be counterproductive, weakening nature rather than strengthening it. I discovered that there is a scientific backlash going on against the simple formula that natives are good and aliens bad.

There are horror stories of alien takeovers, of course. Most of them happen on small, remote islands with only a few native species, where carnivorous rats, cats and others hop off ships

and cause mayhem.

But elsewhere, most of the time, the tens of thousands of introduced species usually either swiftly die out or settle down and become model eco-citizens, pollinating crops, spreading seeds, controlling predators and providing food and habitat for native species. They rarely eliminate natives. Rather than reducing biodiversity, the novel new worlds that result are usually richer in species than what went before.

When invaded by foreign species, ecosystems don’t collapse. Often they prosper better than before. The success of aliens becomes a sign of nature’s dynamism, not its enfeeblement. Nature’s desperadoes are proven colonists and exploiters of the ecological mess that humans leave behind them. So surely that makes them nature’s best chance of healing the damage done by chain saws and plows, by pollution and climate change. Far from being nature’s destroyers, aliens may be its reinvigorators, its salvation.

The demonization of alien species says more about us and our fears of change than about them and their behavior. Understandable love of the local, the native and the familiar—of an imagined pristine environment before humans showed up—too often becomes fear and hatred of the foreign and the unfamiliar.

We often think of life on earth as made up of complex and tightly knit ecosystems like rainforests, wetlands and coral reefs that are perfected and stable, with every species evolved to have a unique role. Today, fewer and fewer ecologists believe nature is either stable or perfectible. Real nature, they say, is often random, temporary and constantly being remade by fire, flood and disease—with species coming and going, fitting in, adapting or losing out.

In this vision of nature, alien species are just like any other. Whether brought by humans or in more traditional ways, they are not an intrinsic threat to ecosystems. They are part of nature doing its thing.

In fact, as true environmentalists, we should rejoice when species burst through the paving stones of our cities, or wash up on foreign shores. We should celebrate nature’s powers of recovery. We should let it run wild. How else are species to thrive and respond to the disruption of our activities, including climate change, if not by invading new territories, by becoming aliens?

We should stop trying to turn one moment in the past into an ossified museum relic. The new wild will be different, but no less dramatic and wonderful than the old wild. Alien species, and the novel ecosystems they inhabit, will be at the heart of it.

We should bring them on.