During the darkest days of the Great Depression, the logging city of Tenino, Washington, created a complimentary wooden currency to help locals survive the economic crisis.

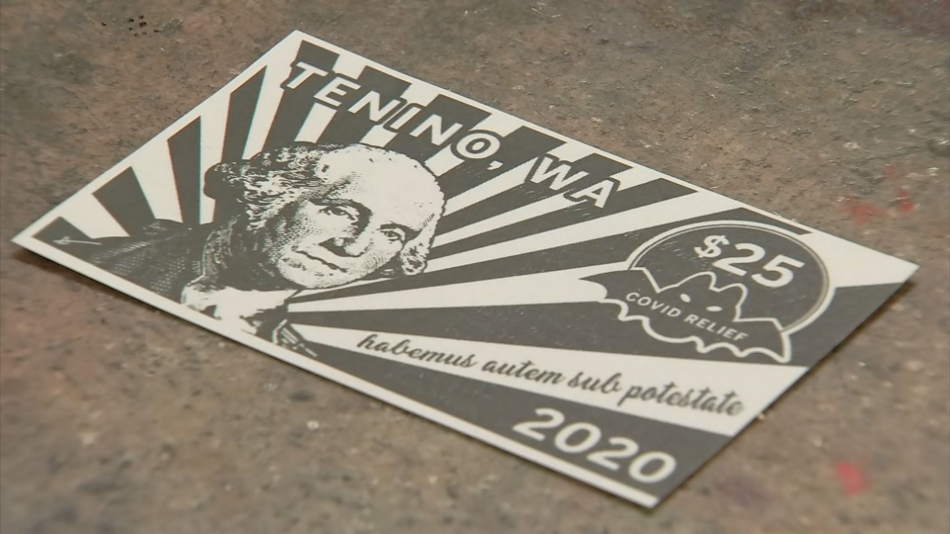

Now, almost 90 years later, the town is once again “printing money” on postcard-sized sheets of maple to help locals suffering from financial hardship. Pegged at the rate of real U.S. dollars, the currency can be spent everywhere from grocery stores to gas stations and child care centers, whose owners can later exchange them.

“It worked perfectly,” says Tenino’s mayor Wayne Fournier, whose new scheme offers residents who demonstrate they are experiencing economic difficulties caused by the pandemic a stipend of up to $300 a month in wooden dollars.

Now you might be asking: how can a city just make up its own currency? Well, these currencies aren’t actual replacements of real money. They are so-called complementary currencies — a broad term for a galaxy of local alternatives to national currencies.

According to research published in the journal Papers in Political Economy in 2018, 3,500 to 4,500 such systems have been recorded in more than 50 countries across the world. Typically they are the localized currency that can only be exchanged among people and businesses within a region, town, or even a single neighborhood. Many are membership programs limited to those who have signed up for the scheme; they typically work in conjunction with rather than replacing the official national currency.

They take many different forms. Relatively few are based on paper money; many are now purely digital or are exchanged via smart cards. Their goals also can span multiple economic, social, and environmental objectives. Some complementary currencies aim to protect local independent businesses. Some promote more equal and sustainable visions of society. Others have been founded in response to economic crises when traditional financial systems have ground to a halt. As the coronavirus pandemic brings on a wave of social and economic tumult, all three challenges appear to be in play at once.

In Tenino, which has a population of less than 2,000, the wooden money is printed using an antique 1890 Chandler & Price letterpress. Since the launch in May, cities from Arizona to Montana and California have been in contact with Tenino for advice about starting their own local currencies.

“We have no idea what is going to happen next in 2020,” adds Fournier. “But cities like ours need to come up with niche ways to be sustainable without relying on the larger world.”

Want to read more about how complementary currencies work? Look no further than here.