A team of researchers from Northwestern University has developed a revolutionary temporary pacemaker that is absorbed by the body once it’s no longer needed.

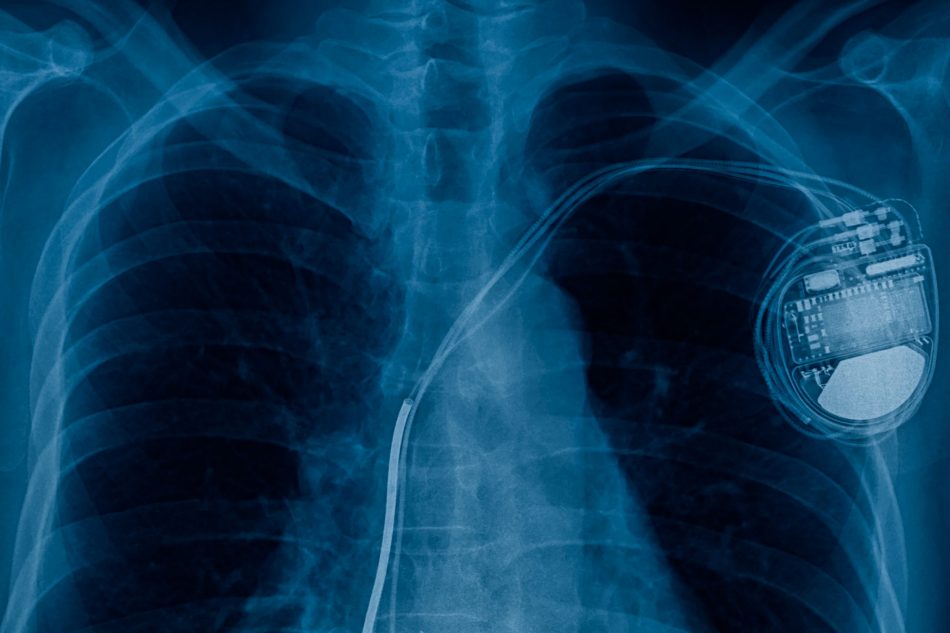

Pacemakers are incredible devices that are implanted in patients’ bodies to help regulate their heartbeat. The first pacemaker was implanted in 1958, and since then millions of people have benefited from them.

Some need permanent pacemakers, but those who require them for only a span of a few weeks or so, like patients who have just undergone open-heart surgery, may face some complications. Temporary pacemakers have external power supplies and control systems that may be accidentally dislodged, posing an infection risk. Plus, the heart tissue is prone to damage during removal.

These potential problems may soon disappear with the introduction of the newly developed battery-free, dissolvable pacemaker. The device, which will cost around $100, is implanted directly on the surface of the heart but can be controlled and programmed from outside the body.

It’s made of materials that are not only compatible with the body but will undergo chemical reactions that allow them to dissolve and be absorbed over time. These include magnesium, tungsten, silicon, and a polymer known as PLGA. The final product is thin, flexible, weighs less than half a gram, and looks like a minuscule tennis racket.

It’s powered by wireless technology in which radio frequency power from an external device is sent to a receiver within the pacemaker. This power is then converted into an electrical current that is used to regulate the heart. According to Professor John A. Rogers, who is part of the team that developed the absorbable pacemaker, similar technology is used in the wireless charging of smartphones and electric toothbrushes.

For now, the device has been tested on the hearts of mice and rabbits, slivers of human hearts, and within live dogs and rats. Based on the results from the trials with dogs, the system demonstrated its ability to generate the power transfer necessary for the device to be used in adult humans.

In the rat trials, the device was in operation for four days. Scans at the two-week mark revealed that the device was starting to break down, and at seven weeks it had been completely absorbed by the rat’s body.

The results from the trials are all very promising, but there is still a lot of work to be done before the device is ready for human patients. After more testing and tweaking is done to ensure that it is safe and effective, this device will allow for an easier recovery for patients after cardiac surgery, and could even mean that patients avoid ending up dealing with permanent pacemakers unnecessarily and instead be left with a strong and healthy pacemaker-free heart.